How women can optimize cortisol levels to enhance energy and preserve muscle mass

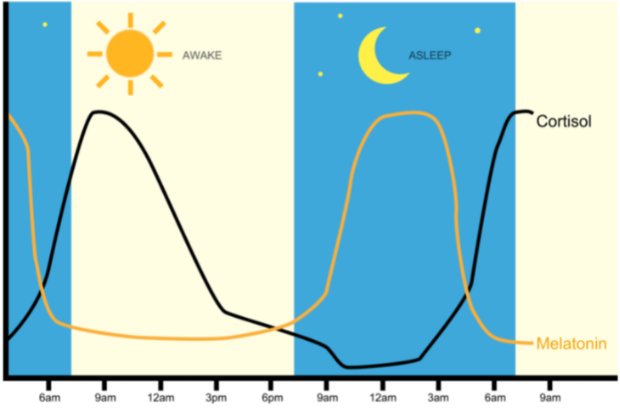

“Chrono-nutrition” is an emerging field that aims to understand how timing of food-intake may impact our health by affecting our circadian rhythm. This 24-hour “master” clock affects several hormones, including insulin, cortisol, epinephrine, melatonin and growth hormone. Each day, we experience an episodic release of cortisol under normal sleep-wake conditions. Cortisol crosses the blood-brain barrier so the body can enter states of readiness and alertness. In anticipation of waking, cortisol naturally peaks in the morning (the ‘active’ phase) to enhance arousal and our drive to eat, then declines throughout day until levels fall to their lowest point shortly after falling asleep1. This is why higher levels of cortisol at night may be associated with poorer sleep quality and explains why cortisol can be a double-edged sword: we want it elevated at the appropriate time, but not too much or for too long. In a similar fashion, melatonin shifts our rhythm to align with environmental cues of light and darkness and promotes the onset of sleep1.

Image: Normal, healthy diurnal cortisol rhythm

External inputs such as light and food heavily influence our circadian rhythm2. For example, viewing sunlight within the first 30 minutes after waking, for 2-10 minutes, has been shown to improve focus, mood, energy levels 3,4, and learning throughout the day, as well as prevent a late-shift in cortisol. However, variations in cortisol associated with food intake represent the most robust circadian rhythm in mammals 1.

Eating before exercise has been well documented to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS) during the workout and maximize the ‘anabolic window’— the period when muscle blood flow is greatest and when muscle is most sensitive to nutrient uptake. Some research indicates that ingestion of amino acids and carbohydrate pre-workout may have a greater effect on MPS and performance compared to post-workout5. Conversely, eating post-workout may be more of a critical time for reducing muscle damage and enhancing recovery.

Unsurprisingly, literature in this area is largely amassed from male subjects, despite distinctive physiological differences between males and females. During resistance training (RT), females burn less carbohydrate and more fat, likely due to hormonal differences5. Accordingly, fueling strategies for women—which are heavily based on data from men— should be met with caution.

Pihoker et al. evaluated the effect of consuming protein and carbs before and after strength training— or not at all—on strength adaptations and body composition in trained, young females5, and the metabolic adaptations that followed training for 6 weeks. The women consumed a shake either 15 min prior, after, or not at all (control) comprised of 200 kcal, 25g protein, 16g carbohydrate and 3.5g of fat. It was found that women who ate before lifting weights burned significantly more fat 30 minutes after the session, relative to eating post-lift or not eating at all 5. In addition, upper body strength was more responsive to eating before OR after lifting (versus not eating at all).

TRE (time restricted eating)/ fasting

Studies that examined changes in circadian rhythm during Ramadan (fasting from sunrise to sunset) revealed that the normal biphasic pattern of cortisol was totally abolished. During Ramadan, significantly lower morning cortisol7 was observed along with higher nighttime cortisol8. But what about less extreme versions of fasting, like simply skipping breakfast?

When breakfast is consumed, cortisol steadily drops6. Eating your first major meal of the day likely resets cortisol patterns, so when this reset fails to occur, peak cortisol concentrations persist for longer than normal10. The literature in general shows omitting any meal from the day will shift the diurnal curve of cortisol to the right1. An important study showed that women who skipped breakfast four times a week or more has significantly elevated cortisol throughout the mid-day and early afternoon10. What’s more— they displayed a blunted (or flat) diurnal cortisol pattern. This same disrupted rhythm has been linked to cardiometabolic disease risk factors, such as insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, and high blood pressure10.

It’s well understood that fasting (to the point of glycogen depletion) triggers gluconeogenesis in the liver (the production of glucose), and cortisol and growth hormone control this process. Whenever blood sugar is low, cortisol goes up- and if we fast for too long, it’s considered a stressor. Quite simple, this is a survival response whereby the body will utilize stored energy to maintain blood sugar.

So— while fasting can be a diet strategy with impressive results on body composition for some groups of people— fasting will drive up the sympathetic nervous system in perimenopause, as baseline cortisol levels are already profoundly greater due to declines in estrodial and progesterone 6. Fasting before high intensity exercise (i.e, HIIT, sprints, running) will exacerbate cortisol in these women, and black coffee without food before an intense session will elevate both morning glucose spikes, as well as cortisol.

Accordingly, my evidence-based recommendations for all females are as follows:

Daily, for perimenopausal women: Eat 15g protein within 30 mins of waking up.

30 min before an early morning weight training session: eat a 15g, ideally 25g protein snack5. This may increase resting metabolic rate (excess post-oxygen consumption) over the course of the day, as well as improve muscle recovery.

30 min before an early morning, high intensity cardio session (involves sprinting, running, or heart rates > __% HR max): eat a snack with at least 15g carbohydrate and 15g protein. The inclusion of carbohydrate blunts cortisol in the bloodstream and provides an actual fuel to maintain blood glucose levels (*and because protein does not serve as a fuel)!

Sources

- Chawla,S. et al. Review: The Window Matters: A Systematic Review of Time Restricted Eating Strategies in Relation to Cortisol and Melatonin Secretion. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2525.

- Manoogian, E.N.C.; Panda, S. Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 59–67.

- Blume, C et al. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie 2019 · 23:147–156

- Terman JS, Terman M, Lo E-S, et al. Circadian time of morning light administration and therapeutic response in winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:69–75.

- Pihoker, A. et al. The effects of nutrient timing on training adaptations in resistance-trained females. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 22 (2019) 472–477

- Fiacco S, Walther A, Ehlert U. Steroid secretion in healthy aging. (2019) 105:64–78

- Bahijri, S.; Borai, A.; Ajabnoor, G.; Abdul Khaliq, A.; AlQassas, I.; Al-Shehri, D.; Chrousos, G. Relative Metabolic Stability, but disrupted Circadian Cortisol Secretion during the Fasting Month of Ramadan.

- Haouari, M.; Haouari-Oukerro, F.; Sfaxi, A.; Ben Rayana, M.C.H.; Kâabachi, N.; Mbazâa, A. How ramadan fasting affects caloric consumption, body weight, and circadian evolution of cortisol serum levels in young, healthy male volunteers. Horm. Metab. Res. 2008, 40, 575–577.

- Quigley, M.E.; Yen, S.S.C. A mid-day surge in cortisol levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1979, 49, 945–947.

- Witbracht, M.; Keim, N.L.; Forester, S.; Widaman, A.; Laugero, K. Female breakfast skippers display a disrupted cortisol rhythm and elevated blood pressure. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 140, 215–221.

At a Glance

Meet Our Team

- Nationally renowned female orthopaedic surgeons

- Board-certified, fellowship-trained

- Learn more